The Connection Between Electricity Governance & Social Change in Pakistan

Are some Karachi neighborhoods more difficult to bring social change in than others ?

Dear friends from the governed world,

Reading Ijlal Naqvi’s1 book, Access to Power2, introduced me to an entirely new idea: Using the management and governance of electrical infrastructure to understand a state’s, in our case, Pakistan’s, ability to act over its territory. “Can the state actually do what it says it will ?”3 Ohh. Can the state not do what it says it will?

This is relevant to us — you and me — who are interested in making social change (or simply helping others) in Pakistan.

Running a school for street kids in Bhangoria goth, Karachi, was extraordinarily hard. In contrast to doing something in, say, my own neighborhood with a better education rate and presence of government. Naqvi’s work helped me see my personal experiences from a higher vantage point, supported by research and data. And I found the answer to a question I had been asking myself: Why is it more difficult to operate in some neighborhoods of Karachi than others?

***

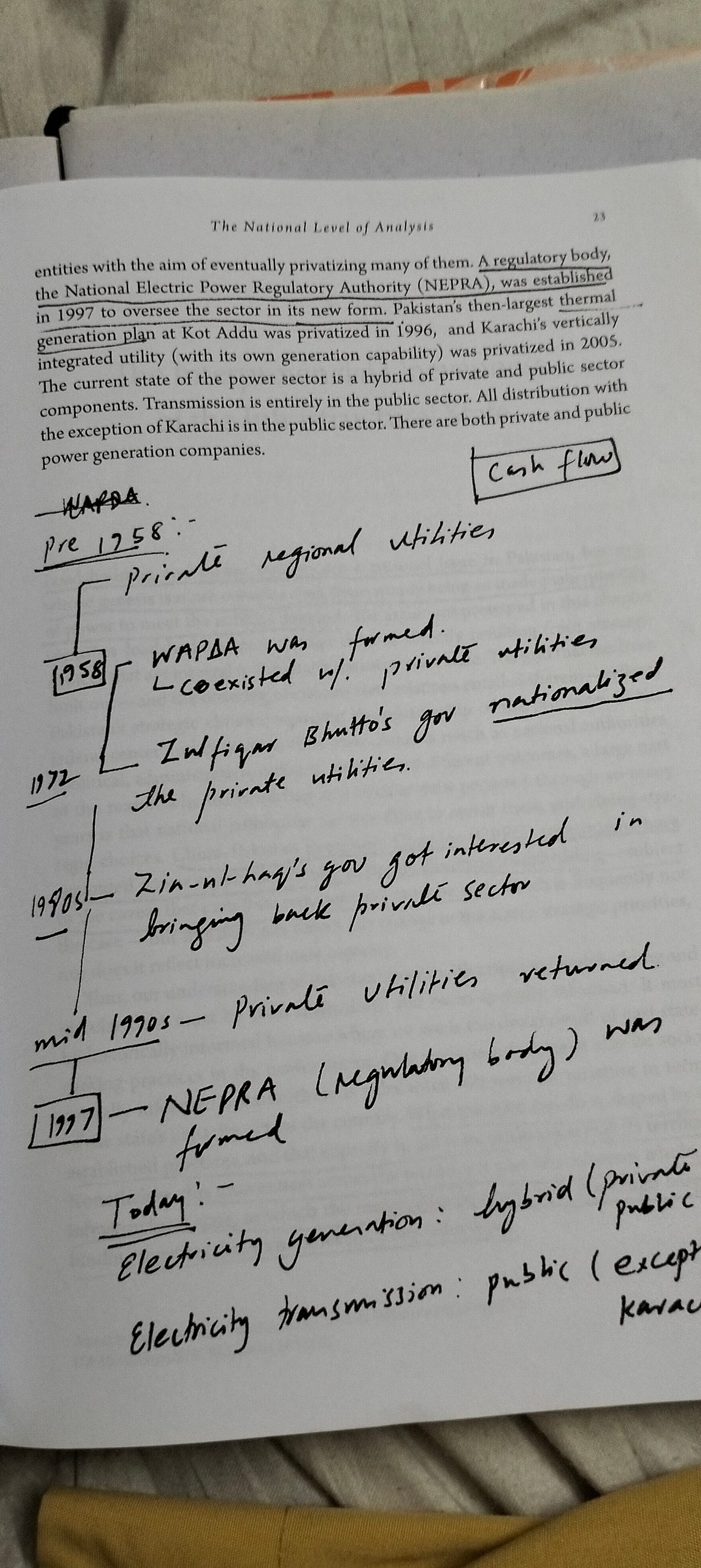

Naqvi uses the electricity transmission and distribution losses as proxy indicators for the state’s uneven ability to “penetrate society and implement projects across its territory.”4

He shows that the commercial losses are lowest in the province of Punjab, where electricity consumers pay their bills to a greater extent than the rest of the country. Balochistan and interior Sindh, on the other hand, have an electricity bill non-payment rate of 75 and 64 percent, respectively. But these are the regions where electricity generation is situated.

We may expect the government to treat losses as a flaw. But these losses are a “strategic choice taken by the federal center to accommodate the realities of Pakistani state making.”5 Naqvi calls it ‘inequality by design.’

“… high losses persist in interior Sindh and Baluchistan because these frontiers and unsettled regions … are not deemed amenable to settlement. The federal center chooses not to expand the necessary effort — military, economic, ideological — to subdue and integrate resistance in the region.”6

And this choice of the government to not enforce governance can be seen in Bhangoria goth and other similar neighborhoods.

Bhangoria goth is built on illegal, unauthorized land. The underprivileged residents are mostly tenants, whose fixed rent includes their electricity payment. (A fixed payment raises the question of whether the landlord is using a legal electricity connection.) The uneducated tenants generally do not interact with utility companies and, hence, lack basic training to work with others in a formal setup with rules and processes.

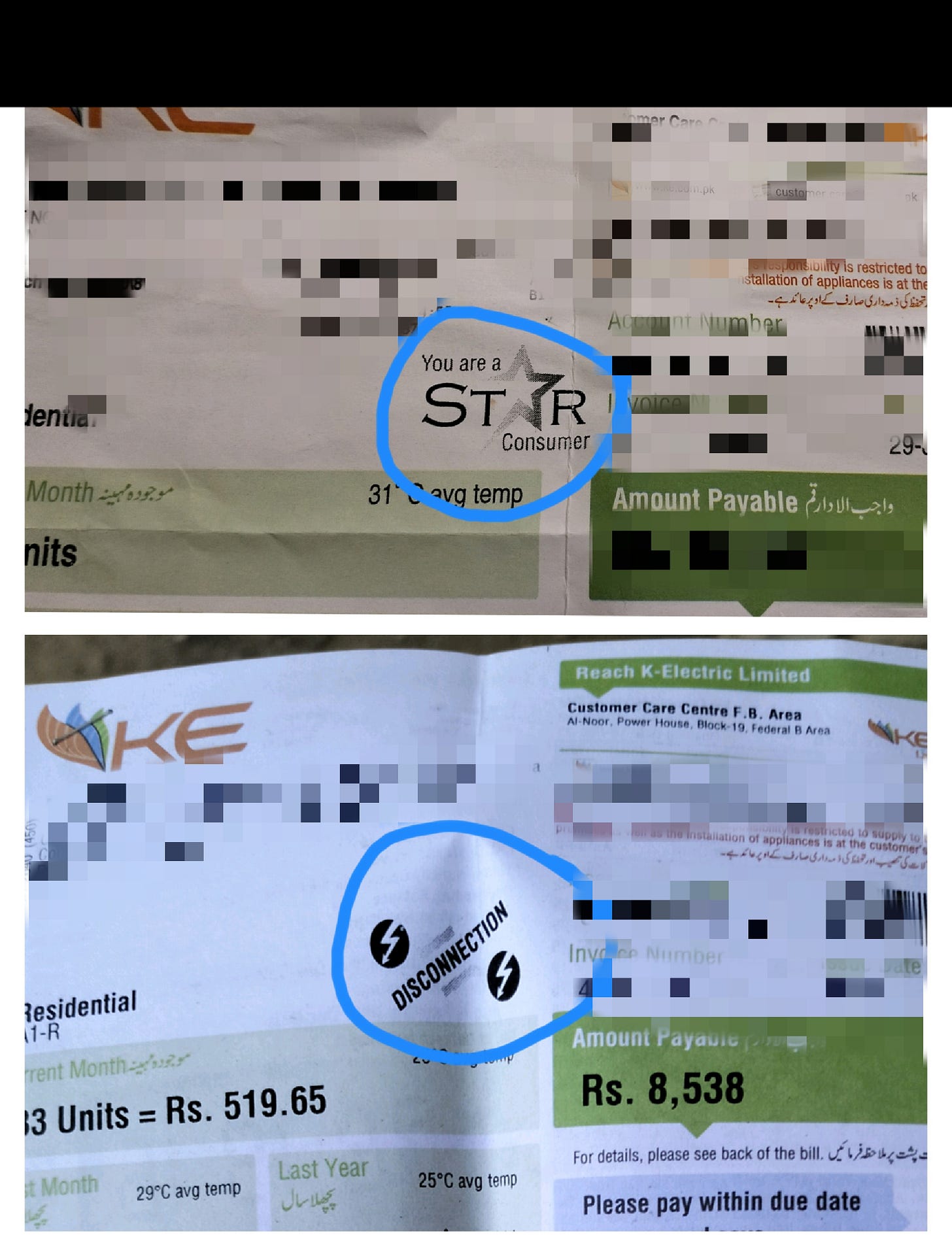

Both our multimillionaire school landlords, both factory owners, had electricity bills stamped with “Disconnection” by K-Electric, due to nonpayment of previous bills. (Unlike the bills from my neighborhood, where K.E. usually bestows consumers with the title of “Star Consumer” for paying bills timely. )

The summer electricity loadshedding happens daily and is also higher in the goth and the adjacent Muhammadi Colony than in other, more affluent neighborhoods. (Higher loadshedding usually means the electric company penalising localities with higher nonpayments of bills and electricity theft.) This sounds like another example of Naqvi’s ‘inequality by design.’

We all intuitively understand that the government’s authority is uneven across Karachi (and Pakistan), but now, academic research has put it into words and supports it with data. If the state, with all its might, is unable to force its will and is choosing to let the governance slack, then the non-profits, NGOs, and concerned, active citizens should take note of it.

The next time I’d have to operate in a new neighborhood, I aim to pay attention to the management and governance of electricity in that area. That will be one indicator (of many) to guide my actions and solutions for that neighborhood.

*****

If you wish to support my work in less-governed, underprivileged neighborhoods, then please share this post or consider subscribing. Spreading the word about my work and learnings will help me continue.

[Update 16/04/25]: The author Ijlal Naqvi kindly shared his thoughts on this article. Here’s an excerpt from his response that might be of use to the readers :

I don’t write about Karachi in my book because KE is under private management. That said, I do think that there are parallels to be seen in that some parts of the city—such as the goths—are less integrated into the state, and that this represents inequality by design in the way I describe for other parts of Pakistan (and you have picked up from the book). I have a separate paper on Karachi that uses data from KE which you can find here7. That research was curtailed by covid, but the maps for the Karachi paper are far superior to what I was able to do for my book.

Ijlal Naqvi is an Associate Professor of Sociology at Singapore Management University. He has a Phd in Sociology from the University of North Carolina. Previously, he has worked as a business consultant for the US and Pakistani governments.

See page 12 in Access to Power.

See page 12 in Access to Power.

See page 30 in Access to Power.

See page 30 in Access to Power.